Tempo Studies on Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony

William Carragan

Contributing Editor, Anton Bruckner Collected Edition, Vienna

December 2007, revised January 2008

Grossglockner, 1918 painting by Edward Theodore Compton

… it was through the unforgettable performances under [Franz Schalk’s] baton that the divine inspirations of this lone Titan of music (for that is the vision that the Fifth conjures up) came to uplift the hearts of all mankind. Surely it is from some lonely eminence that these deeply moving utterances make their tremendous impact upon this world of ours, in all its infinite variety. This symphony reveals the utmost technical mastery of form, structure, and instrumentation. For all who have ever set foot in the mighty edifice of its polyphony, its melodic wealth, and its chorale, it remains an unforgettable experience.

Leopold Nowak, 1951

I wouldn’t write something like this again for anything in the world.

Anton Bruckner

Introduction

General considerations

This paper is one of a series of systematic historical tempo surveys of Bruckner symphonies which has been under way for twelve years. In each case one or another type of analysis is performed on the data collected, whatever seems appropriate. From these studies a number of very interesting tendencies and trends have been discovered, not all of them encouraging. In many cases it appears that the conductor is bemused by the beauty or the impressiveness of the sound at any particular point, and obtains from that what seems locally to be a good effect without considering the global implications of the choice of tempo. Any scrap of Bruckner’s music can almost be counted upon to sound beautiful at any speed. But when a theme is introduced and played at a speed which does not have a logical relation to the tempos used in the surrounding material, one can have no expectation that the overarching unity of the movement will be maintained.

The two-tempo plan for the first and last movements of symphonies, almost universal for Bruckner, is this: (a) Tempo of C theme = tempo of A theme, and (b) Tempo of B theme is not a lot slower. This rule is suggested by many indications in the scores, though occasionally rather subtly. In the finale of the Eighth, however, Bruckner asks in every manuscript and edition that A = 69 and B = 60, which in practice sound nearly the same and give the movement coherence. And when the C theme appears, the first printed edition goes on to specify “Erstes Zeitmass”, thus completely exemplifying the two-tempo rule. But in that movement, conductors routinely use a tempo of A = 80 for the opening measures, and B = 48 for the second theme, which is quite a bit slower. Each tempo sounds good while the music is being played, but the use of tempos so different from each other gives a patchwork texture to the entire movement which destroys its unity. When the C theme enters, it cannot easily be played as fast as 80, and the unity of the movement is further impaired.

The first movement of the Fifth is even more complex. Here there seems to be the necessity of establishing a three-tempo plan, with an adagio tempo for the introduction in addition to the two tempos needed for the exposition. So one would have A = C, with B being somewhat slower, and the adagio tempo of the introduction being quite a bit slower. (This same scheme would apply to the finale, though in that movement the adagio tempo is used only at the beginning of the movement without seeming to recur twice as it does in the first movement.) In this survey, fifty recordings were heard straight through with tempo measurements made at 21 salient points, and in most cases, a three-tempo scheme seems to have been the idea of the conductor. The details, however, are of infinite variety, as Nowak suggests in his remarks accompanying his edition of 1951 (which was a slight revision of the Haas edition of 1935). They will be the subject of this account.

Groups and Graphics

I have arranged the fifty recordings in the study into groups for discussion and comparison. Graphs showing the tempos through the movements have been prepared for each group, as follows:

Group A (early): Böhm 1937, Zillig 1947, Abendroth 1949, Pflüger 1951, Andreae 1953

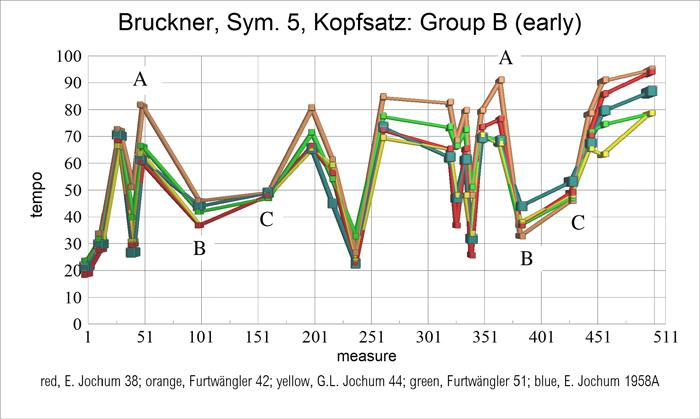

Group B (early): E. Jochum 1938, Furtwängler 1942, G.L. Jochum 1944, Furtwängler 1951, E. Jochum 1958A

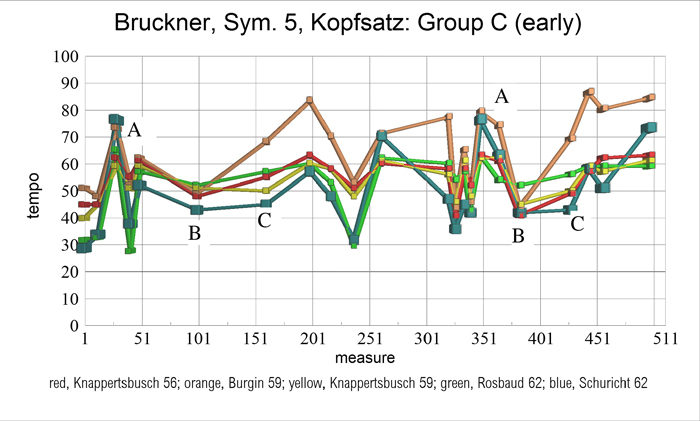

Group C (early): Knappertsbusch 1956, Burgin 1959, Knappertsbusch 1959, Rosbaud 1962, Schuricht 1962

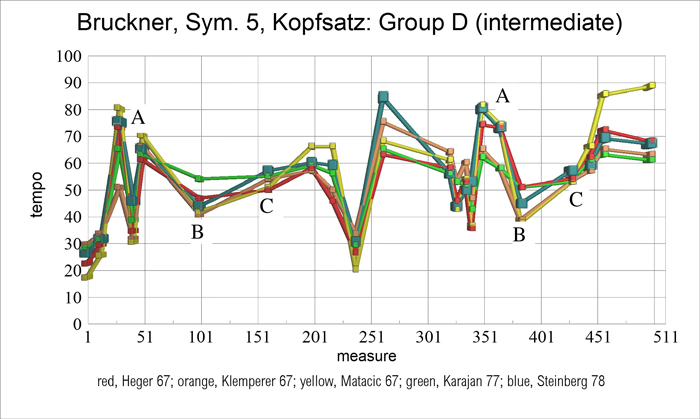

Group D (intermediate): Heger 1967, Klemperer 1967, Matačić 1967, Karajan 1977, Steinberg 1978

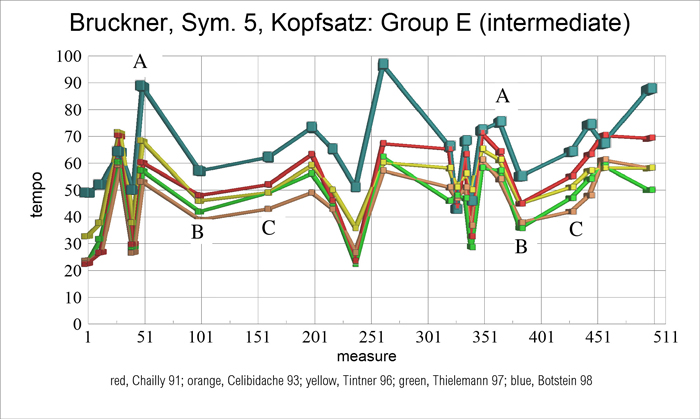

Group E (intermediate): Chailly 1991, Celibidache 1996, Tintner 1996, Thielemann 1997, Botstein 1998

Group F (recent): Blomstedt 2006, Metzmacher 2006, Welser-Möst 2006B, Harding 2007, Zander 2007

There are over 200 recordings of the Fifth in my archives, covering every performance of which there is an available recording. These could not all be analyzed at this time, and there have been omissions of many distinguished Brucknerians which is regrettable. But the survey provides such a torrent of information for scrutiny that one hardly feels deprived. The graphical presentation enables one to see many fascinating features of these recordings at a glance, and in particular one can sense immediately whether one or another structural requirement is being met. In particular, I will make the point that the introductory tempo should be used again at the beginning and ending of the development, and in the graph one can see whether that is indeed being done. And one can see whether the A theme material is being taken at a consistent tempo in the exposition, development, and recapitulation. In the following paragraphs, I will discuss certain of these issues in detail.

The attached graphs show the tempos used by the different conductors in the first movement. Use the arrow symbols to scroll among the groups, and click on a specific graph to enlarge it.

The Pizzicato Chorale

Bruckner is fond of the sound of the chorale, and uses chorales or hymnic passages very frequently. They are normally played by the brass, in the Fifth for example at measure 18 of the first movement, and most famously, at measure 175 of the finale. I wrote a paper on this subject for the Bruckner Journal Conference in 2005, and in that paper listed and described examples from nearly every symphony. In that connection I called attention to the chorale nature of the pizzicato texture in the B theme of the slow movement of the Fourth Symphony, which in many performances is hardly audible as a backdrop to the viola melody. But when played legato on the organ, that sequence of chords is quite clearly a chorale in tetrameter. It has an eerie familiarity for a Bruckner enthusiast who recognizes it but cannot place it, never having heard it sound quite like that. Of course the voice-leading is impeccable! Thus the finale of the Third is not the only place where a chorale and a separate melody coexist in Bruckner’s writing. Now in the Fifth there is a similar situation in the B theme of the first movement, where there is a four-phrase pizzicato chorale in a type of Sapphic meter with a melancholy theme, separately entrusted to the first violins playing with the bow on the G string, beginning in the third phrase. Again the chorale is barely detectable in many performances, but Bruckner’s admonition in the Third to have the chorale predominate could very well be applied here as well, especially as it would give the entire Gesangsperiode a much better shape. To emphasize this point I have written out the chorale as a hymn and ventured to supply words for it taken from a hymn text in a recent edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern which seems appropriate to this moment in the symphony. If the conductor simply makes sure that the first violin and the basses always play their notes clearly and distinctly, the chorale should be perceptible to the ear.

Symphony no. 5, Kopfsatz: Chorale in exposition

The Heger Score

Several years ago I was able to obtain the Haas conductors’ scores of the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies which had belonged to Robert Heger (1886-1978), an opera composer and conductor whose career was in Vienna, Nürnberg, and Berlin, and after the war, at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. He also conducted at Covent Garden for ten years. These scores are full of the most detailed tempo information, very intricate though sadly without metronome markings. I have laid out the markings in the first movement of the Fifth, parallel to those in the Schalk score (in which the movement is complete though somewhat re-orchestrated) and to those in the Nowak score based upon Bruckner’s composition score. It can be seen that Heger was attempting to enter into the somewhat bare Haas score the nuances and traditions to which he was used, as an aide-memoire while conducting. While the Schalk score was all that he had been able to experience heretofore, he did not accept its suggestions uncritically, particularly in the tempos to be used during the development as will be described below. By great good fortune, we also have a recording of a performance of the Fifth by the Danish Radio Symphony led by Heger. While the recording dates from 1967, when Heger was already 80 years old, and the marks in the score are presumably from the time of the score’s publication in 1935, there is a quite close correspondence between the score and the recording. The two resources together provide a unique document of the development of the tradition of Bruckner conducting.

The First Movement

Two or Three Tempos?

If one tried to perform this movement with only two basic tempos, one would have to say one of the following: (a) A = C = B with the introduction tempo slower, or (b) A = C and B = introduction. There are a few performances in the survey which by and large carry out one or the other of these ideas. For example, exemplifying choice (a), Karajan 1977 (BPO) has A = 63, B = 54, and C = 55 to 59, which are substantially equal, with the introduction slower at 32, but faster in its recurrences, and Harnoncourt 2004 (VPO) is similar with A = 59, B = 54, and C = 60, even closer to being equal, with the introduction at 31. Rosbaud 1962 is similar, with rather little slowdown for the B theme. On the other hand, following choice (b), Wand 1991 (NDR SO) has A = 64, B = 41, C = 57, and introduction = 32 at first but equal to B when it returns. These performances have their adherents, but in contrast to those with a clear three-tempo plan, they seem quite pallid. These conductors seem quite unwilling to engage the A and C themes as both loud and fast; instead, they are preoccupied with the monumentality of the sound, which is one of those characteristics that sound good by themselves but don’t help to keep a twenty-minute movement going. It is really too bad to expect that whenever the music gets loud, that it will also get slow and heavy, especially in this piece where there is a theme, the great brass chorale at measures 18 and 338, which really must be rather slow and heavy, and very loud! One would like to have the rest of the loud music offer some sort of contrast. At the same time, the B theme at 54 sounds rather hurried with both Karajan and Harnoncourt, with the nuances and cadential rallentandos seeming to be too deep and somewhat awkward.

Schalk seems to be of the three-tempo persuasion, but he complicates the picture with directions to get slower in the development at letter L ( measure 283) and again at letter M (measure 303). Quite a number of performances do that, whether from the influence of Schalk or from sheer inertia it is hard to say. These performances will be discussed below, but in this context, one can say that the characteristics of the various themes, and the interplay between them, depend critically on the maintenance of tempo. Bruckner is often accused of bombast, which is really only believable if the loudness seems to be there only for its own sake, to try to impress and maybe deafen the listener. If instead the listener hears loud music at certain times deriving from the inner nature of a theme heretofore played softly, as one does with A1 played softly at measure 51 with its loud version, A2, at measure 79 at exactly the same fast tempo, the accusation of bombast is much less likely because the sound is exemplifying the form within the theme group. This idea goes back to Beethoven and Haydn and perhaps before, and we may be completely confident that Bruckner was totally aware of that. Unfortunately many recordings slow down for A2, even if the A1 tempo is not itself particularly fast. (This effect was not measured systematically and is thus not shown on the graphs.)

The Three-Tempo Plan Triumphant

The three-tempo plan is almost certainly what Bruckner had in mind for both the first movement (Kopfsatz) and the finale, and it underlies the great majority of the recordings in the survey. The following descriptions take that fact as a basis, though not for granted.

Tempos in the introduction. The only explicit tempos are for the beginning, Adagio, for the Intro4 theme, at measure 31, which in Nowak is intended to adumbrate the tempo of the beginning of the exposition: Bewegter, im künftigen Allegro-Tempo. (in the Allegro tempo to follow), and for the renewed Adagio at measure 43. Schalk has, instead, Allmählich bewegter (gradually faster). There are a few early conductors who accelerate in this passage, particularly Furtwängler, Zillig, Abendroth, Pflüger, and Burgin, the last playing from the Schalk score. In the introduction, it is possible to do that since the acceleration is cut off at measure 43 by the adagio theme Intro5 (an evolute of Intro3 which never recurs). But in the recapitulation, at letter N, an acceleration, if taken, would lead directly to the loud version of the A theme, and thus should be started at a slower tempo, as seems to be suggested by Schalk in the introduction. This matter will have to be left to the discretion of the conductor, though it must be said that an acceleration here is very exciting. Meanwhile, it should be said that Intro2 should not be significantly faster than Intro1, which of itself should be a true adagio without being too slow. After all, the time signature is cut time (2/2), which suggests a certain amount of energy.

Dynamics in the introduction. Many conductors begin this symphony with inaudible pizzicatos. Pizzicato strings are one of only two instruments which can be played arbitrarily softly; the other is the kettledrum (the timpani). It is unwise to begin the symphony inaudibly. There should be a very perceptible beginning; Heger writes “leise aber deutlich” in his score. One has plenty of time to play loud later. For example, the great chorale, Intro3 at 18, should be brilliant and martial, with plenty of sound from everybody but especially the tuba. And controversially, it should be just that same way at measure 338 in the recapitulation; see the extensive discussion of this point below.

Tempos in the exposition. Zander 2007 seems to be crystallizing on A = C = 69 and B = 50. This A and C tempo avoids the sluggishness of Harnoncourt, for example, without reaching for an A tempo which would be impossible for C as Botstein does. The B theme should move as fast as possible without giving any hint of hurry, but no slower than 50. Heger marks “beschwingt” (exhilarated, transported) at measure 109 where the arco melody begins. In this movement, there is a complication with two C themes, and in Zander 2007 C1 (measure 161) is only a bit faster than B, with plenty of room for a dramatic acceleration to the A tempo for C2 (measure 199). There is an Allmählich belebend (gradually faster) in the Schalk score at measure 189 which expresses this effect, but it is all right to begin the acceleration four measures sooner as Jochum does again and again, very subtly, if one desires.

At measure 130, at a solemn moment in the Gesangsperiode, Schalk places episemas (tenuto marks) over four quarter notes in the first violin part. At the parallel passage in the recapitulation, measure 402, there are no episemas, but observant Schalk-influenced conductors, and some others like Harnoncourt who can hardly be called Schalk-influenced, add them anyway. There are similar markings in the slow movement of the Second, presumably put there by Bruckner, but they should not be used as an excuse to play the passage especially slowly or with excessive nuance.

In the codetta, at measure 217, there is a downward scalewise progression of chords that is a clear Bruckner signature. It occurs quietly in the first movement of the Second and the last movement of the Ninth, and elsewhere in his symphonies and vocal writing. It is possible that this chordal scale is related to the sleep motive from Die Walküre which is explicitly quoted in the Third and the early version of the Fourth, and it is almost certainly the source of the great brass chorale of the finale of the Ninth. (See my paper on the chorales, “Bruckner’s Hymnal”.) This great importance in Bruckner’s oeuvre prompts certain conductors to take a little time here, and Schalk seems to have the same thought with his poco rall. in measure 220. When done subtly, as it usually is, the effect is quite gratifying.

Dynamics in the exposition. The eexample shows the pizzicato chorale of the B theme, clearly demonstrating the excellent voice-leading. The style is clearly that of a hymn, and as mentioned above I have supplied words, written after Bruckner’s death, which fit the meter of the chorale almost exactly, and besides that, are a reasonable expression of Bruckner’s own view of his work. The example should convince one that the accompaniment needs to be thought of as a chorale, as independent as the chorale is in the famous passage in the Third. In particular, the top voice of the chorale should be brought out, even and especially when they are marked ppp. It is easy to play this music too softly or too slowly, but if one does, a lovely melody and a profound effect go unrealized. One can pronounce the words set to the chorale at half note = 50 or 54 to test the tempo.

Tempos in the development. The extra cadence beginning at measure 231 should not be too slow! The movement does not come to rest here, and the recapitulation of the introduction theme Intro1 which immediately follows should be something of a shock. The tempos of Intro1 and Intro2 should be just as at the beginning, and we will later apply this same requirement to the recurrence of Intro3 and Intro4 at the beginning of the recapitulation. Here we see the operation of Bruckner’s preferred analytical scheme, Part I and Part II, with Part II simply being an expanded and developed recapitulation of Part I. As Bruckner matured, he came closer and closer to having a truly flexible Part II, where the recapitulation of the B theme was preceded by a very brief true recapitulation of only the last part of the A theme group. And in the Fifth, all but one of the elements of the introduction are cited in order: Intro1 at 237, Intro2 at 241 and 259, Intro3 at 338, and Intro4 at 347.

Between these elements of the introduction lies a good deal of research into the synergy of A and C, at the brisk tempo characteristic of those themes. The fast part of the development begins at measure 261, Schalk’s J, where Allegro is written above the staff. Then at measure 283 (Nowak’s L), Schalk writes Etwas langsamer (somewhat more slowly), and at measure 303 (Nowak’s M, Schalk’s L), Noch breiter (yet more broadly). By contrast, Nowak seems to indicate that there is no tempo change necessary here. But non-Schalk conductors, which is to say most people especially younger ones, get a bit slower through this passage just to accommodate the very dense writing at 319. Older Schalk-influenced conductors, like Jochum, Schuricht, Matačić, and perhaps Steinberg, get a lot slower, as does Botstein. I don’t like it much. Perhaps those markings were put into the score in analogy with similar indications in the finale of the Seventh, which definitely do come from Bruckner. But the slow-downs in the Seventh are in the finale, adding grandeur where it is needed, but here in the Fifth, much earlier in the composition, they create a heavy or turgid effect. In his score at measure 303, Heger at first writes “Etwas breiter [somewhat more broadly] (Schalk)”, but later crosses it out and writes “besser dasselbe Tempo beibehalte” [better keep close to the same tempo]. It is typical of him that he would have carefully considered both alternatives, and then felt independent enough of Schalk, whom he must have known in Vienna, to make his own decisions.

In Schalk, there is a fermata at measure 325, just before the obligatory short mention of the B theme which begins in the brass, and another fermata at measure 331, Schalk’s M, just before the B theme in detached woodwind chords and pizzicato strings. These fermatas are a really good idea and could be thought of by anyone just on the basis of the music. In these detached B-theme chords near the end of the development, at 333½ there is often a speedup agreeing with Schalk’s poco accel., and at 335½ a slowdown agreeing with Schalk’s poco rall. This is done by nearly everyone and might also be somewhat automatic. But there is no indication in any score to get slow for the B theme citation. Schalk says to get slower for the B theme, in the exposition at measure 101 with Langsamer (slower), and in the recapitulation at measure 381 with Wieder langsamer (still slower); at 325, all he says is sehr ruhig (meaning very quiet and slow), which Bruckner occasionally uses as a combined indication of tempo and dynamic. So we should not be surprised to find no indication here in Nowak.

Tempos in the recapitulation. The recapitulation may be taken to begin with the statement of the first-movement brass chorale at measure 338 (Intro3). Here there is no indication for a slow tempo in either Nowak or Schalk, though on musical grounds it is very difficult to imagine that theme at anything but a slow tempo. I believe that the generally-incomplete state of editing of this work, combined with Schalk’s inconsistencies, give ample room for the nearly-universal practice of taking measure 338 at the same tempo as measure 18, that is, in the region of 32 or so. Harnoncourt’s tempo of 49 at this point will be difficult for most people, especially considering that his A theme tempo is barely faster. Abbado 1998 also has a fast tempo here for the chorale, and his pizzicato citation of B at 333½ is almost as fast as his A tempo, sounding rather matter-of-fact.

The theme I have called Intro2 occurs with an explicitly-marked Adagio tempo in the Nowak score at measure 15 and 23, and again, Adagio, at measures 241 and 259, but it also serves as the motor for the development at the Allegro tempo, beginning at measure 283 with its latter half expanding into a brilliant cascade of counterpoint at measure 303, as well as in the coda or “second development”. But that use of Intro2 does not make it appropriate to take Intro3 at a similarly fast tempo at 338. In Mus.Hs. 36693, Bruckner’s notation of a tempo at 338 cancels the riten. at measure 335. At the most this notation means that the tempo of Intro3 is the same as that of the B theme, measure 101 or measure 325. It is not a sufficiently strong piece of evidence to justify an allegro tempo anywhere in this passage. Dohnányi’s 1991 performance, with its tempo for measure 338 being 50, a bit faster than his B theme tempo, shows the effect of this kind of thought. Rather than being martial and stirring, it merely seems perfunctory. It impairs an otherwise logical and sensitive performance with a wonderful tearaway coda.

Should the B theme be slower in the recapitulation than in the exposition? Some of the older conductors seem to think so, in a way making up for the fact that the Gesangsperiode is only 44 measures long in the recapitulation compared with 60 measures in the exposition. Indeed there is a sense of Schalk’s Wieder langsamer which could be used to justify taking the theme slower the second time through. But I see no need for that, and also there is the potential of destroying the subtle unity of the movement which must be assiduously developed in the listener’s ear.

Tempos in the coda. In the Schalk version, a fast tempo for the coda requires that the acceleration marked at 437, intended for C2 at 441, be carried through continuously, through the beginning of the coda at 453, to Beschleunigtes Zeitmaass (accelerated tempo) for the peroration at 493. There is no special marking at the beginning of the coda itself. Most conductors like to get fast here, sometimes very fast (Furtwängler, Eugen Jochum). Fast is good, but clarity is good too, and all the details of the writing, which involves the ornate rhythm of Intro2, should be clearly audible at whatever pace is taken. Heger writes very stern instructions for himself at measure 453: “l’istesso tempo / (nicht zu rasch! an den Schluß des Satzes denken! keine Stretta!”. That is, “The same tempo, not too fast! Think of the end of the movement! No tightening up!” And at measure 493, the peroration: “Hauptzeitmaß / l’istesso tempo,” or “Principal tempo, the same tempo.” Yet in the recording he takes a quite fast tempo at that very measure 453, presumably holding that very piece of paper in his hand, which he had not previously reached in the movement. Of course this could represent the cumulative effect, on one man over many years, of many conductors like Jochum who liked to conduct the coda at a speed not previously encountered in the movement. And he did not get as fast as Jochum did.

Dynamics in the coda. Every once in a while, someone tries to apply some degree of nuance to the great forte-fortissimos of Bruckner’s perorations. For example, in an otherwise superb performance of the Fifth dating from September 5, 1998, at measure 497, four measures into the peroration, Abbado suddenly drops back to an mf, and then has a final crescendo to 501 where the violins go up an octave. The coda already has quite a bit of detail and dynamic variety, and it doesn’t need this extra fillip. Schalk, for all the changes he imposed on this piece, says nothing of the sort. He writes ff at 493 and ff sempre at 497 and thus is much closer to Bruckner’s intentions, although few will give him credit for it.

Recommendations

(1) The symphony should begin at 32 or 34 beats per minute to the half note, (66 or 69 to the quarter note), with the opening pizzicato (significantly audible, please!), the fanfare, and the chorale all at the same tempo. For the gathering theme (measure 31), one should start at about 60 to the half note and accelerate to 69, but no farther. The last chorale (A major) should be at 32 again. One should re-attain 69 for the tempo of the real A theme at measure 51. That tempo should be kept strictly through soft and loud until the long decrescendo (with double-dotting) that leads to the B theme; here there can be a gradual deceleration.

(2) One should make sure that the tempo of the B theme is above 50, but good and flexible nuances should be built in, gracious and not too deep, but very natural-sounding. Things should not be overdone at measure 129 and at measure 401 in the recapitulation. The pizzicato chorale should indeed sound like a chorale.

(3) The C1 theme starts imperceptibly faster than the prevailing tempo of B. The acceleration begins subtly at measure 185, and in earnest at 189, reaching an honest 69 at measure 199; one should not be content with anything less. The codetta, measure 209, can be a bit slower, especially the scale at measure 217, but the energy will die out if too much time is spent in the quiet area.

(4) For the development, the pizzicato and fanfare are at 32, and the A theme at a bright and perky 69. When the A theme tempo is established for the second time, at measure 261, the tempo should be held firm right through measure 324, and again for 329-330. This takes a lot of grit. The secret is not to start too fast–not a bit over 69.

(5) At the end of the development, the allusions to the B theme, measures 325-328 and 331-337, should be at the basic 52. However, it is traditional to make an acceleration during the pizzicato, and then a rallentando. Heger describes that in detail. The fanfare is strictly at 32! It doesn’t say it in the score, but nothing else will do.

(6) The recapitulation is like the exposition. One doesn’t need to play the B theme any slower than in the exposition. The acceleration in the C theme must be carried out swiftly because there is not much time. One must re-attain 69 at measure 441.

(7) The coda can start at 72 and go to 80 or more, or it can be played through at 76 which is probably safer and just as effective. This is very fast, but the audience will love it.

The Adagio

General comments

In entering the world of the slow movement one encounters a different place, a place where the dynamic purposefulness of the sonata form is replaced by the static mood-painting of the song form. Bruckner’s adagio form comprises five parts, A B A’ B’ A” with coda, or simply ABABA, a five-part song form. Although each thematic recurrence is considerably developed, it is as if Bruckner is exploring the self-realized ramifications of each theme rather than causing them to reveal their nature through satisfaction of the demands of a well-known paradigm. What this means in performance is -9- that the conductor must direct the music without imposing artificial externalities on it, while at the same time giving its emotional possibilities free expression. Unlike the sonata-form movements, this five-part form has few parallels–the slow movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the Heiliger Dankgesang of his quartet in A minor, and the third movement of Mahler’s Fourth, are among the very few examples of this form outside Bruckner (see “The Bruckner Brand, part 2”). Thus in the development of a concept for such a movement the conductor has comparatively little to go on , and there is quite a variety among the recordings of the Adagio of the Fifth, with greatly-contrasting conceptions of what the movement is supposed to be like.

The commonest conception is simply that of a uniform tempo, in which the half note receives the same pulse in all the sections, with perhaps the fifth part, A”, being played somewhat slower in accordance with its greater complexity, and with Bruckner’s somewhat confusing tempo designation. Against this proposal one can make several claims. First: In other adagios written in this form Bruckner specifically asks for different tempos, and in two cases different time-signatures, for the B parts in contrast to the A parts. Second: Even here, the second part has a tempo designation which might be at variance with the simple Sehr langsam (or in the Schalk version Adagio) of the opening. And third: the underlying 6/4 character of A and A’ suggest different relations than that of equality of the half-note pulse, which have made their appeal to certain conductors as we shall see. Nonetheless the idea of a single pulse throughout has the greatest number of adherents, ranging in this study from Knappertsbusch’s reading of 1959 all the way to the Zander performances of nearly fifty years later.

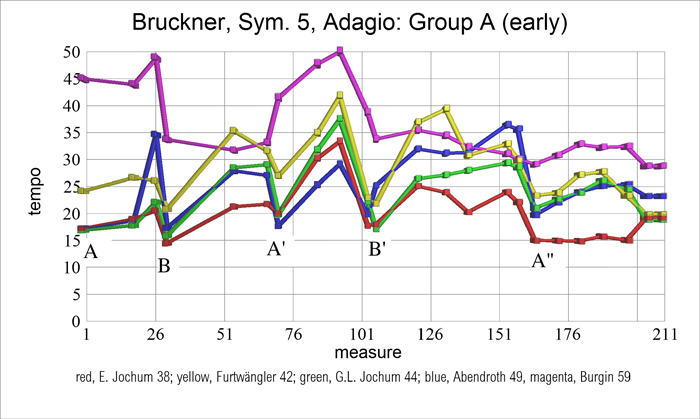

Group A (early): E. Jochum 1938, Furtwängler 1942, G.L. Jochum 1944, Abendroth 1949, Burgin 1959

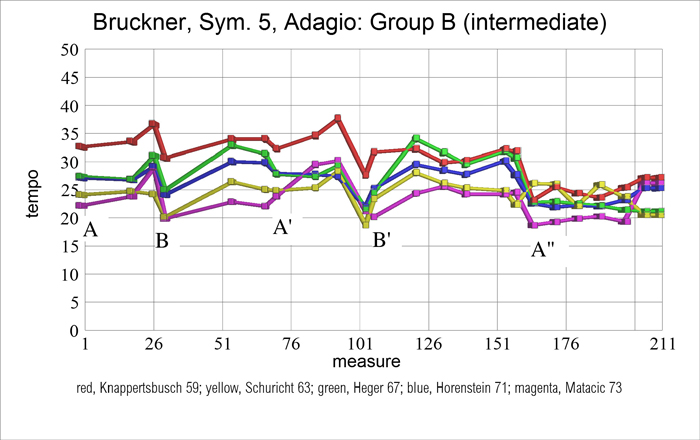

Group B (intermediate): Knappertsbusch 1959, Schuricht 1963, Heger 1967, Horenstein 1971, Matacic 1973

Group C (recent): Dohnányi 1991, Janowski 1991, Celibidache 1993, Tintner 1996, Botstein 1998

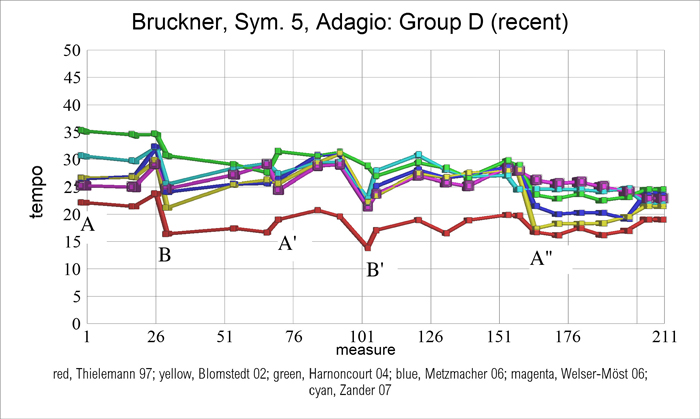

Group D (contemporary): Thielemann 1997, Blomstedt 2002, Metzmacher 2006, Welser-Möst 2006B, Zander 2007

Here are the graphs showing the tempos used by the different conductors in the Adagio. As before, use the arrow symbols to scroll among the groups, and click on a specific graph to enlarge it.

We see a considerable distinction in basic tempo among the studied performances, from the brisk half-note = 32 of Knappertsbusch 1959 to the highly-demanding half note = 18 of Thielemann 1997 and the leaden 15 of Celibidache 1993. Zander 2007 is among the faster ones at 28. Despite these differences, many subtle nuances can be seen in common. For example, almost everyone gets a little faster in the unison writing beginning at measure 23, despite the fact that the material presented there is to be heard many times again, particularly in the last great outburst of part 5. Then at the beginning of part 2, the B theme starts much slower, but as soon as the horns start playing their repeated notes in measure 39 the tempo tends to pick up to a gentle maximum at 55, with the wonderful cello phrase of measures 43-46, which Heger labeled in his score “the beautiful place” (“die schöne Stelle”), played with nuanced elegance and forward motion. At 71 the opening tempo is regained, and continues more or less evenly through part 3 with perhaps a slight acceleration to measure 93 and beyond. The spare and highly-ambiguous transition starting at measure 101 is occasionally played faster than the surrounding music, sounding particularly uncomfortable if the tempo is very slow. In part 4 the B theme begins once more at a slightly slower tempo but the return of repeated notes, this time in pizzicato strings, again invites a faster speed for the return of the beautiful place, now inscribed “die göttliche Stelle”. But for the long dominant preparation serving as the re-transition to part 5, opinions differ, and some conductors get faster, not so much at the beginning of the passage at measure 139, but in the long flute solo which ensues. If the basic tempo is fast enough, this will not place unreasonable demands on either the flutist or the listener, and the tempo need not be rushed. This is actually a great moment, and like the passage beginning at measure 23, it should not be treated with triviality.

Determining what tempo Bruckner wanted for part 5 is not straightforward. His direction is “Beinahe Melodie im gleichen Rhythmus wie im Allabreve-Takte, jedoch langsamer,” or “the melody in almost the same rhythm as in the 2/2 measures, though slower.” Commentators, including Heger in a specific notation, acknowledge that Bruckner meant “tempo”, not what we would call “rhythm.” At this point Schalk says, simply and wisely, “Langsamer.” Some conductors, especially the ones who are already going pretty slowly, do not change the A-theme tempo here. Others, including Zander 2007, do, and at a faster tempo, it seems to be the more musical approach, and gives the gentle rallentando in the preceding flute solo a substantive goal. By contrast, some conductors in this group, such as Dohnányi and Janowski, both of 1991, get a lot slower for part 5, perhaps through an obscure principle of mensural equality (quarter note becomes eighth note), or perhaps simply because they want to. What is less satisfying is the practice of several directors to speed up for the coda, which is commonly done in the Seventh and elsewhere, perhaps as a reaction to the economical texture. At a faster tempo, this unfortunate and illogical choice seems less likely to be made.

Should the tempo be steady or variable?

The common witness in these recordings is that half-notes in the Adagio should be beaten evenly, whether it is divided into two quarter notes as in the B theme, or in three as it is in A and A’, parts 1 and 3. Again and again in the many performances reviewed, conductors seem to be comfortable with a basically smooth and uniform tempo for the first four parts of the movement, a particular example being Horenstein 1971 with a notably sober presentation. But there are those who disagree. For example, Botstein, in his interesting 1998 performance of the Schalk version, seems to feel by contrast that two quarter notes in A, constituting two thirds of the beat, should be equal to one quarter note in B, or half of the beat. To make that true, the tempo in B would have to be three quarters of the tempo in A. Botstein more or less achieves this, with A = 35 and B = 28 or lower in B’ (part 4), but at the cost of an unnervingly rapid A-theme tempo. It should be said that nothing specific in the Schalk score requires this interpretation. Then in 2004, Harnoncourt seems to be trying something similar, but with less consistency and logic. His tempo, initially vigorous, sags continuously through the movement with only a slight recovery for A’ (part 3).

In sharp contrast to these conceptions of uniformity (or adjusted uniformity) are a number of early performances which contain serious alterations of tempo. These particularly include performances recorded by Furtwängler in 1942 and 1951, as well as those of Böhm 1937, Abendroth 1949, the Jochum brothers in 1938 and 1944, Burgin 1959 (from the Schalk score), and Knappertsbusch 1959 which for many years was the only performance of the Schalk score which was generally available. All of these performances feature in one way or another a great acceleration in part 3, beginning long before Schalk’s mild suggestion of poco a poco accel. at measure 98. The effect, particularly when it is underlined by Schalk’s addition of brass and timpani in 95 and 96, is hair-raising. Unfortunately the survey did not include a check point at measure 99, but in all of these cases the tempo is substantially faster than at the already high charted levels of measure 93. Furtwängler exceeds 40 at this point, and Burgin1 nearly reaches 50, which is almost unbelievable. It makes all of part 3 seem like an independent tone poem, even though in starting at the basic tempo at the beginning and returning to that tempo at the end, the interpretations effectively maintain the logical continuity of part 3 with the rest of the movement.

Furtwängler’s unique contribution seems to be the fact that in part 4 he does the same thing. He takes the modest tendency to a faster tempo suggested by the repeated notes at measure 115 and redoubles the effect measure by measure until he is going almost as fast as he did in part 3. The fact that part 4 is quite long in this movement only adds to the effect. And then, especially in the Salzburg performance of 1951, he does the same thing in the somewhat slower Part 5, rising to a level of feverish intensity at measure 179, a daring move attempted by no one else in this survey. Furtwängler has the reputation of an intellectual, but here and elsewhere his work seems to me to be that of a highly sophisticated and cultivated person who has enough technique and insight to be able to make extremely emotional statements which other people, for one reason or another, would not dare to do. Is that sort of thing an intrusion by the conductor? The modern prevalence of uniform-beating performances would suggest so. But I am not so sure. At the end of either of the Furtwängler performances, there is no doubt that the listener has been through a very deep experience, and it sounds like Bruckner to me.

The early style, that of Furtwängler and so many of his contemporaries including Richard Burgin, does not stem from notations in Schalk’s score, except from his lone request for an acceleration late in part 3 at measure 98, far later that the place where a real climax must begin. This style seems instead to be either Furtwängler’s own, assuming the others are consciously imitating him, or, more likely, a common witness from the pre-Haas days of a method of rendering this movement in an emotionally gripping manner. Today, with so much information from the early period not generally available, an excessively slow or uniform interpretation can be seen as an expression of the “Urtext” mentality, which says that if there is no direction in the original source or the score at hand to do something, nothing should be done. But we all know that in the area where Urtexts have been most influential and most beneficial, that of baroque and early music, a very great deal has to be done which is not written down, including the most basic determination of tempos. In the first movement of the Fifth, the Collected Edition score, presumably an Urtext, has no indication to take the B theme slower than the A theme. But it is simply not successful to take the B theme as fast as the A theme, even though only in the Schalk score is there such an indication. Some ideologues might say that the Schalk designation is a perversion of Bruckner’s intent. But people who actually listen to the music realize that a tempo change must be made, and thus the tempo excursions we hear in these early performances cannot be rejected on theoretical grounds. So we are left with the question: does a truly artistic performance require them? Has one not given this movement its due if there is no great climax in part 3, maybe in parts 4 and 5 too?

Where is the high point?

This movement is unusual in Bruckner’s oeuvre in that its part 5 contains no place at which one could say that it reaches a true, decisive highest point, as the adagio of the Seventh does at the necessary and authentic cymbal clash. True, in his score of the Fifth, Heger labels measure 187 as the “Beginn der Steigerung” (beginning of the intensification) and 192 as the “Hohepunkt” (high point), but both are debatable; the intensification surely begins earlier and the high point might be later. Furtwängler’s fastest tempo is already in play at measure 179, but not perhaps the greatest intensity of his feeling, which comes later, all through the loud passage of measures 189–194. Most surprising, the last outburst, at measure 196½, is in the home key, which Bruckner never does elsewhere. These observations lead us to the meaning of the movement, that the A theme is a theme of wandering and alienation, whereas the B theme is a theme of consolation and renewal. In the adagio of the Ninth, one might argue that the same dichotomy is present. But there, the A theme is one of aspiration through agony, and an unattainable bliss which Bruckner barely glimpses beyond the Cross. Here in the Fifth it is the loss of connectedness to society, manifested through the rootless chains of sevenths heard in part 1. Nothing could be sturdier or more reassuring than the B theme, nothing more lovely and inspiring than the “göttliche Stelle”, but the shadowed flute solo and dominant preparation toward the end of part 4 show us that even that renewal is, in earthly experience, transitory. At the end, the return to the home key while still in the climactic region makes sense simply as a reinforcement of the idea which the main theme is supposed to express anyway. This movement contains no great accumulated climax like that in the adagio of the Seventh, and Schalk did not try to add cymbals anywhere here, although his brass additions in part 3 certainly enhance the effect. Jochum says in his essay “The Interpretation of Bruckner’s Symphonies”2 : “The weight of significance carried by the movements of a symphony must be taken into account in the interpretation, that is, the interpretation must relate everything to the climax. In the Fifth Symphony, for example, it must direct everything towards the Finale and its ending, and, important as the first three movements are, continually keep something in reserve for the conclusion.”

In part 5 of the slow movement, the cellos and basses play in groups of three notes, slurred together. This is a technique used previously in the Second Symphony, first movement, C theme. Here in the Fifth, nothing sounds more like trudging through mud than to play the slurs over only the first two notes. Perhaps it is true that string crossings make the completion of the slur awkward, and after all, the movement is indeed about wandering. But I would suggest that whatever could be done through special fingerings or bowings to make the slurs strong and even across all three notes would be beneficial to the effect of the piece.

The Scherzo

In the scherzo, the fast tempo (for the A theme, urgent scurrying) and slow tempo (for the B theme, party time) should be consistently different, with the accelerando from slow to fast, B theme to closing group, being very precise. It is easy to set an A-theme tempo at the beginning which is so fast that it can never be reattained; many conductors do that, but it should be avoided. One should also resist the desire to accelerate in measures 229–236, where the B theme material is developed. These measures are definitely part of the slow music, the Ländler, and must be kept that way. This movement is in full sonata form and despite its manic character, it should be played with the seriousness which that form invokes. In the trio, the dynamic changes bring a sort of dark humor into an otherwise lovely and sunny idyl.

The Finale

The finale, like the first movement, has three integral tempos: those of the introduction, of the A and C themes, and of the B theme. But the implementation of the three tempos is much simpler than in the first movement, simply because (a) the introductory tempo is never recapitulated or even revisited, and (b) because most of the movement is at the A theme tempo anyway.

The B theme, though derived from the B theme of the scherzo, is no longer a drunken carouse, but a gracious melody with elaborate and lyrical counterpoint. So much is evident from the greater harmonic stability of the first two phrases. It should be distinctly slower than the tempo of the A theme, which in turn must be regained for the C theme with bold precision.

After the C theme, one should not play the first chorale, measures 175–196, too fast. The pizzicato notes in 192–193 and 215–216 should be clearly audible. The chorale should be stately but not ponderous, and one could speed up a bit at 196 for the lovely codetta for strings. At the end of the movement, as Tovey said of the end of Beethoven’s Op. 110, the tempo must be as steady as the stars in their courses and everything will take care of itself.

The Coda of 1876

Discussion

The composition score of the Fifth Symphony, Austrian National Library Mus.Hs. 19.477, is a veritable battleground of creation and revision. In it Bruckner recorded all, or nearly all, of the work he lavished on this, his most elaborate production. We know that he finished the symphony, composing the movements in order, and then went over all of it, roughly in reverse order, making many changes including metrical revision and the addition of the tuba. Because all of the work is in one manuscript, and because he had no copy scores made until both the original work and the revision were finished, it is mostly impossible to isolate a coherent score which could be called an early version, without the tuba and the metrical revision. However, according to the Haas/Nowak critical report, the coda of the finale has an identifiable early version in a separate manuscript, Mus.Hs. 3162. Much of this early coda, comprising the crescendo to the chorale, is printed in the report. Other indications point to the deletion in revision of two later measures, one just before the chorale and one at the end; these can be restored. In 1997, I was asked by the Shunyukai Orchestra of Tokyo to prepare the early coda for performance, which I did, adding the tuba for consistency with the rest of the symphony, but not adding the two measures out of a principle of non-interference. It was to be understood by listeners that the result was an experiment in which the fascinating development of Bruckner’s thought could be experienced. A recording was made of that performance. Recently I have gone over my score of 1997 and added the two measures, also providing Bruckner’s metrical numbering in as many as three layers.

A great deal could be said about the differences between the late, familiar coda of 1878 and the early version of 1876. For example, in the crescendo of the late version, Bruckner took pains to make the phrases more regular in length, and his work is especially apparent in these locations:

first outburst 1876: mm. 506-514 (7+2) 1878: mm. 506-513 (6+2)

second outburst 1876: mm. 523-528 (6) 1878: mm. 522-525 (4)

third outburst 1876: mm. 529-536 (5+3) 1878: mm. 526-531 (4+2)

In these places alone, the early version gains five measures. Two more measures are picked up in the final crescendo. But in the chorale itself, the situation is different. This table shows the result:

transition 1876: mm. 571-590 (8+8+4) 1878: mm. 564-582 (8+8+3)

chorale (first 2 phr.) 1876: mm. 591-606 (8+8) 1878: mm. 583-598 (8+8)

chorale (last 2 phr.) 1876 mm. 607-622 (8+8) 1878: mm. 599-613 (8+7)

It can be seen that in his revision of the most significant passage in the symphony, the moment of its utter culmination, Bruckner stepped away from regular phrase lengths of 4 and 8 to create irregular ones of 3 and 7. One could argue endlessly about the merits of this move. But I must mention that ever since I heard this symphony for the first time fifty-four years ago, to the present, I have personally felt that in this greatest of all symphonies, the coda seems to come one measure too soon, and the last phrase seems to be one measure too short. It strikes me with amazement that Bruckner deliberately created these anomalies.

Haas’s Notes on the Coda of 1876

[Introductory note by W. Carragan. The composition score of the Fifth, Mus.Hs. 19.477, contains nearly all the labor that was done on this symphony, both in composition from March 3 through November 7, 1875 (movement order 2, 1, 3, 4) and in revision up to January 4, 1878 (movement order 4, 1, 2), according to Nowak’s chronology in the revised critical report of the Collected Edition.3 All the work is in one place, layered and superimposed measure by measure. As a result the study of early versions of individual measures is nearly always possible, but the establishment of a coherent early version, in which all of the measures would be presented in the form which they had at one time, is a distant hope if it is possible at all. Fortunately, there is a separate manuscript for a very significant part of the finale, that is, the great crescendo or intensification which leads to the chorale. This is Mus.Hs. 3162, mentioned above, and it was reprinted by Haas in the critical report.4 My version of the crescendo is a practical edition of that publication, with the only change being the addition of the tuba in the passages exactly parallel to those in the late version where the tuba was used. This was done in order that the early crescendo could be used with the rest of the symphony; the tuba was added by Bruckner during the composition and revision of the finale. Here is Haas’s description of the situation.]

Haas: As for the Finale, the National Library eventually received a manuscript (Mus.Hs. 3162) containing bifolios 21 through 23, corresponding to measures 503 through 570 of the main version (Mus.Hs. 19.477). This is a fair copy on the same paper as the main version, with full indications for performance, which strongly differs from that version in important features and individual details of orchestration and represents a significant early stage of the work. Accordingly the full text of these six leaves must be included, reaching from measure 503 to measure 577, thus containing seven more measures than the final text.5 Of course the bass tuba is completely missing in these bifolios. The primary changes affect the following places:

1. The transition of measures 511–514 (shorter in the main version, 511–513) which later was recreated with one measure less. Measures 512–514 are crossed out in pencil and show traces of work in pencil.

2. Three interjectory passages, which were later struck out, namely the two-measure echo passage 527 and 528 (main version, after 525), and two extensions each of one measure, 533 (main version, after 529) and 536 (main version, after 531). Here beneath early version 527 and 528, as well as 533, there is a cross in red ink, with at 533 another one like it in pencil above the system, and above 536 a cross in pencil, leading to a corresponding later metrical numbering of the cited measures.

3. The intensification and eventual decrescendo in measures 548–552, which later at the time of numbering was displaced backward by half a measure, and was reworked in the deployment of energy with great restraint. And, finally,

4. The great intensification of 553–570 (main version, 548–563), as it later flows forth, is shortened by two measures, and especially in the last eleven (later nine) measures considerably revised. In measure 553 the horn call is harmonized differently in the later measure 548, and in measures 554- 560, in the first half of the measure, the horn calls as well as the contour [movement] of the first violin do not always agree completely with measures 549–555 of the main version. In further course the harmonic sequence was changed.

The instrumentation is also changed outside these described passages; only the string body remained quite unchanged, with the bass line almost completely so. The winds are strongly relieved [thinned out] at measure 508 and 514-517 in the main version, the trumpets and trombones developed at 506 and following, the woodwinds at 506 and following doubled, and at 508 and following independent. The dynamic intensification is accomplished after main version 524 more slowly than earlier, while in the early version a crescendo of register is first developed, in the main version there is a sudden leap into fortissimo at main version 522. The orchestral textures of measures 523–526 and 529–532 is similarly taken over from the later passage of 571–577 (main version 522–525, 526 to 529 and 564–570, although in the later refinement quite elegant individual passages were entered, such as the trumpet upturn in main text 513 and following and 527 and following, or the proud announcement by the horns at main version 565 and 569. Among later contrapuntal insertions one could mention the third trumpet at main version measures 538–541, also the wind at this same place, as an important melodic polishing where the G in the cello part at main version measure 535 in opposition to the earlier C sharp in the violoncello and bassoon at 540. Finally it must be mentioned that letter X was entered earlier, at measure 515 (main version 514), rather than at 522 in the main version.

[Further note by W. Carragan. This description does not do justice to all of the detail in the earlier version which was removed in the later version. One need only consult the intricate counterpoint in early version 553–560 which was excised in main version corresponding measures 548–555. Also in the early version the pedal F was added in the contrabass 12½ measures earlier than in the late version, giving greater solidity to the texture in the earlier version. Lastly, at measure 512–513 in the late version, the horn plays the first movement theme first upright, then inverted, which has always seemed aimless and indecisive to me. But in the early version there are two separate entrances at measures 514 and 516 which accomplish the same thing in a much more deliberate and logical manner. Perhaps to be associated with these changes, although possibly at a slightly later stage of work, is the cancellation of two measures in the material following the great crescendo. One of these would have been the twentieth measure of the prologue to the chorale, thus giving that prologue the symmetrical shape of 8+12 measures in the early version, and the other one would have been the thirty-second measure of the chorale itself, giving it the symmetrical shape of 8+8+8+8 measures. Here is Haas’s brief account, using the measure numbers of the main version.6

Haas: After [main version] 582 a measure was struck out7 , over the system stands gilt nicht (does not count). At 582 it says under the system in ink NB Choral neu, and at 583 under the system in pencil Corn 3 u. Fag. (third horn and bassoon), at 602 above the system in pencil Oboi Clarinetti neu, at 603 in pencil Alles neu, and at 609 under the system repetirt (repeated) is rubbed out, at the measure repetition signs had been made, but they are rubbed out. Finally, at 618 there stands under the system in pencil Violinen neu, and below that Violen.

Update. Since the writing of this paper in 2007/2008 the musicologist and enthusiast Takanobu Kawasaki has gone through both manuscripts, Mus.Hss. 19.477 and 3162, and prepared a conjectural early version of the Fifth Symphony. As said above, the many, many debatable areas in 19.477 which show Bruckner’s diligent composition and revision superimposed on each other can not be said with assurance to have the locally early version contemporaneous with the situation in even the adjoining measure. Nonetheless, Kawasaki’s version is filled with interesting variants and is well worth repeated listening and careful study. It has been recorded by Akira Naïto and the Tokyo New City Orchestra, who have undertaken many interesting Bruckner projects, and issued by Delta Classics. This recording should be in the collection of everyone who is the least bit interested in Bruckner’s methods.

Richard Burgin

During most of the season Richard Burgin, 64, sits unobtrusively at the violin section’s first desk of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, as he has for the past 36 years. But unlike most other concertmasters in the U.S., Polish-born Richard Burgin gets two or three weeks a year on the podium. Last week he led the Boston Symphony at Manhattan’s Carnegie Hall, in a concert of Vaughan Williams, Beethoven and Shostakovich, which he delivered with craftsmanship and no melodrama whatever. “I know what I want, I know how to tell them what I want, and they give it to me,” he said, adding as an afterthought: “just as they give it to any other conductor, only maybe to me a little quicker.”

Burgin has a legendary memory for music. Many times he has saved the situation when a conductor lost his place—by simply playing on until the maestro found himself again. In the words of the late Felix Weingartner, Burgin says: “As long as even one piccolo is playing, we don’t give up.” He says: “I know many virtuosos and I do not envy them. They tell me what it’s like to play the same few pieces over and over and know they have to go here and then be there. Not for me. I like the orchestra.” Next week, after his spell in the limelight, Concertmaster Burgin will be back at his accustomed chair in Boston, marking the bowings efficiently and playing his passages beautifully.8

As a non-musician I feel unqualified to make a considered statement, except to say that this symphony is far more complex than I had previously thought, and feel less surprised as to why it does not get performed that often, as it presents an enormous challenge. I was greatified to see the reference in the artcle as the greatest symphony ever written. I hope to read it again more than once and try to glean more details gradually. This seems to be a major exposition, and the literary style commands respect. Thank you very much.

Thank you for your kind words! The Fifth was so complex that Bruckner himself said he would never do anything like it again, and the Sixth and Seventh, for all their great inspiration and formal innovation, are on a smaller scale. But with the Eighth and Ninth he went back to the monumental proportions of the Fifth.

One wonders why conductors follow so many different tempi in this symphony, particularly in the Adagio. Bruckner says, “Adagio – Sehr langsam,” but some conductors like Harnoncourt, Barenboim and the dreaded Venzago play this as an Andante at a fast clip. How can this be? Are they reading the same score? This article is a jewel at giving you some insight into the choices a conductor has to make. The case of Eugen Jochum is particularly fascinating:

21:20 (1938, Hamburg)

19:18 (1958, BRSO)

18:55 (1964, COA)

18:36 (1969, French National Orch.)

19:16 (1980, Dresden)

21:40 (1982, BPO)

20:48 (1986, COA)

By contrast, his little brother Georg-Ludwig took a speedy approach to the Adagio (17;42 in 1944 with the Bruckner Orchestra of Linz). Eugen seemed to take Bruckner at his word (Sehr langsam) at the beginning of his career, got marginally faster and basically returned to his initial tempo as his career came to a close. This movement contains some of Bruckner’s most eloquent music and I think it benefits from contrasting tempi that are not too disparate (less is more as conductors like Carl Schuricht loved to demonstrate).

Thank you so much Bill for a wonderful article and for your dedication to all matters related to our beloved composer.

Ramon (11.X.2022, on the 126th anniversary of Bruckner’s passing)