What Happened to the Sixth?

A comparative study of the first publication and the Collected Edition of Bruckner’s Sixth Symphony

Louis Cameron Lohraseb

State University of New York at Geneseo

A paper delivered at the Eighth Bruckner Journal Readers’ Conference

Hertford College, University of Oxford, Oxford, England April 12, 2013

Kustodenstöckl, Vienna image via abruckner.com

While Bruckner scholarship often is concerned with the different versions of a particular symphony that were generated by the composer, the Sixth Symphony has its own problems even though Anton Bruckner created only one version, in 1881. It is indeed unique: the only completed symphony never to have been performed in its entirety during the composer’s lifetime and never to have been revised by the composer, indeed brought to print posthumously without the supervision of the composer. Thus the modern interpreter of the Sixth is left with many questions on how best to present this masterwork. Broadly speaking the Sixth has been published in two editions, the first edition prepared by Cyrill Hynais and then further edited by Josef Schalk and published three years after Bruckner’s death (Universal Edition, 1899), and the manuscript-based Collected Edition (International Bruckner Society, ed. Robert Haas, 1937, ed. Leopold Nowak, 1952). My examination of the first and final movements in the first edition version and the Collected Edition (using the Nowak score) has resulted in a list of over 2000 differences between the two publications. In the list I grouped the first, second, third, and fourth instrumental parts together when applicable, and have not taken into account differences in abbreviation (e.g. “rit.” versus “ritard.”). When dealing with differences in placement of dynamics or expressions, I have used discretion. Also in this paper I have used the piano-tuners’ convention for pitch, whereby the cello’s lowest note is C2, and middle C is C4.

Tempos in the first movement

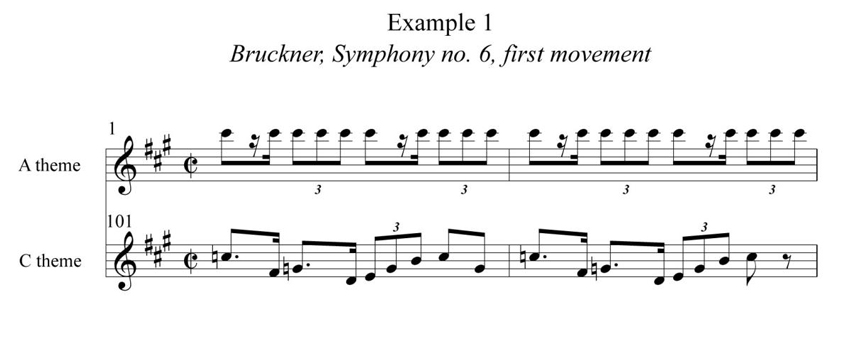

The principal defining characteristic of the first edition is the presence in it of a large number of specific tempo indications and tempo alterations intended to be helpful to an effective rendering of the symphony. Such indications are far rarer in the manuscript and accordingly are not in the Collected Edition either. For example, in the first movement, the Collected Edition lacks a tempo marking at the beginning of the third theme group, leading most conductors from the past and present to play this music at around the tempo of the second theme group, which is marked in both publications “Bedeutend langsamer,” that is, “significantly slower”. Structurally, the movement is made to sound both more logical and more vigorous if the third theme group in both the exposition and the recapitulation is taken at the tempo suggested in the first publication, “Gemäßigtes Hauptzeitmaß,” that is, “moderated principal tempo”. Now the music which begins the third theme group (mm. 101–110 in the exposition, mm. 285–294 in the recapitulation) consists of a brilliant set of rising sequences that create an exhilarating effect, missing if the tempo is too slow. Each measure out of the ten derives in rhythm from the first theme accompaniment and in contour from the first measure of the section, m. 101, as shown in example 1. The problem with not returning to a moderated principal tempo as is called for in the first publication is that at a slow tempo the music sounds heavy and dull, its relationship to the first theme being lost, leading audience members to doubt the coherence of the work. The first publication gives the conductor as much guidance as one could need in this particular passage, writing at m. 101 under “Gemäßigtes Hauptzeitmaß” the modification, “etwas breit,” (somewhat broad, but presumably not as broad as the previous second-theme music) and even writing at the top of m. 105 “etwas belebend” (somewhat more lively or energized) at a location where the harmonic rhythm is accelerated fourfold.

Then at m. 110 and m. 294, the first publication writes “poco riten.”, followed by “Ruhig beginnend, dann ein wenig belebend,” (beginning quietly, then a bit more lively). While the latter indication works well with the material, one must be cautious of the “poco riten.” in both measures 110 and 294, because of the reorchestration in that measure emphasizing the last repetition of the sequential pattern. However, using Bruckner’s original scoring of that measure, the “poco riten.” is not as needful, but still can be observed. In fact, all of the additional tempo indications in the first publication not only provide the modern performer with evidence as to how this music was performed in Bruckner’s day, but also help to focus and clarify the form of the movement.

Tempos in the fourth movement

The form of the fourth movement, which is in essence a typical Bruckner sonata movement of three independent themes, has many elements which make it elusive, in particular the absence of the A1 theme from the recapitulation, surely due to the fact that that theme is utilized throughout the development especially toward the end. Thus, while there are twenty-one additional tempo markings in the first movement of the first edition, the final movement contains no fewer than forty-five additional tempo markings.

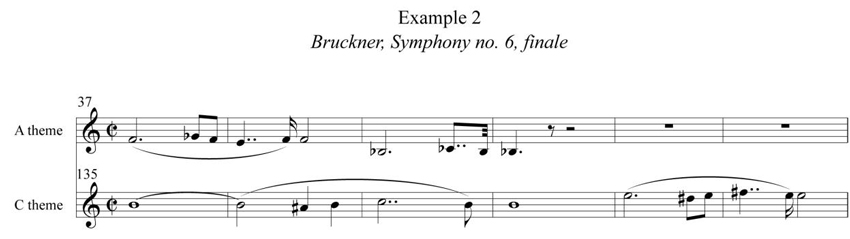

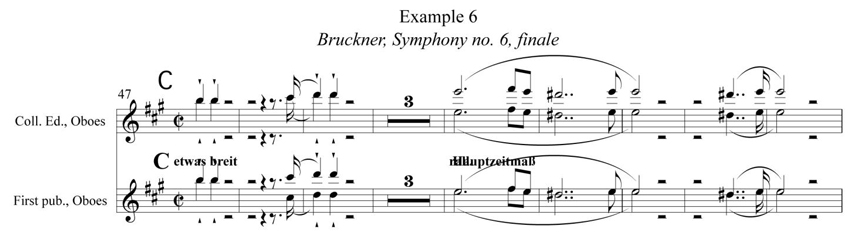

In that movement’s first theme group, the first edition does not provide many tempo alterations save for the marking of “etwas breit” at m. 47, at rehearsal letter C well within the A2 theme, followed by a “rall.” and a subsequent “Hauptzeitmaß” in m. 53, all missing from the Collected Edition. Those indications explicitly help to serve the music, and indeed many of today’s conductors play the music much that way even though using the Collected Edition. It is in the second theme group, beginning at m. 65, rehearsal letter D, where the first edition has many new tempo markings. At the start of the section there is the indication of “Gemäßigtes Hauptzeitmaß”, which is lacking in the Collected Edition. If the beginning of the movement is taken with a certain amount of brio, then this second theme group would be served well by a moderated tempo. The first edition goes on to give very detailed instructions, indicating a “poco rit.” in m. 72, an “etwas gedehnt” (somewhat stretched or broadened) in m. 77, as well as the additional indication of “accelerando” at m. 113, which leads to the beginning of the third theme group at m. 125, strongly derived from the second half of the first theme, as shown in example 2, which the first edition indicates as “Schnell” (fast). These and other additional tempo indications in the exposition of the finale all serve to bring out the inherent qualities in the musical gestures, and by doing so help the listener understand the formal conception of this often-puzzling work.

The development section is also full of additional tempo indications, which are again very helpful to a proper performance of the work. The Collected Edition has only Bruckner’s original marking of “bedeutend langsamer” (significantly slower) at the beginning of the development, and there is not another tempo indication until the recapitulation, where the Collected Edition indicates “Tempo Imo”. Beginning in the fourth bar of the development with “belebter” (livelier), the first-published edition gives very detailed instructions on how to conceive of the development in terms of tempo. It seems appropriate, for example, that in m. 211 there should be the marking “Sehr gemäßigtes Hauptzeitmaß”, as this is the point in the development, mentioned earlier, that brings back the first theme of the movement. If it were true that this entire development should be conceived at a slower tempo, then this quasi-false recapitulation would fail to achieve its effect. Also particularly helpful is the indication at m. 235 of “nach und nach belebter” (more and more lively) until the recapitulation at m. 245, marked “Im Hauptzeitmaß” (in the principal tempo) in the first edition.

It is interesting to note the differences in both the language and placement of certain markings between the two editions in the passage beginning at m. 356 until the beginning of the coda at m. 371. The “langsam sempre” (remaining slow) present in the Collected Edition in m. 356 is changed to “zögernd” (hesitating, or as performers say, taking time) in the first edition, in addition to a fermata at the end of the first half of m. 358 which is not present in the Collected Edition. The second half of m. 358 also has the indication of “allmählich belebend” (gradually lively) in the first edition, which is five bars earlier than the “accelerando sempre” found in the Collected Edition in m. 362. It would be interesting to test the relative merits of these somewhat different approaches in performance! The additional markings of “Beschleunigtes Hauptzeitmaß” (accelerated principal tempo) at the glorious presentation of the A2 theme in m. 285, and the ritard in mm. 405–406 before the return of the principal theme of the first movement in m. 407 are also welcomed enthusiastically.

Perhaps the most reasonable explanation for the lack of tempo indications in the manuscript of the Sixth, reflected in the Collected Edition, is that this symphony was created right before the great popular success of the Seventh Symphony, apparently leaving the manuscript of the Sixth to be neglected for revision and publication during the composer’s lifetime. That is significant because as William Carragan points out, Bruckner was rather sparing with tempo indications in his manuscripts (Carragan, 2013) and tended to enter them only in rehearsal, as in the Second, or at the time of publication, as in the Seventh. In his own preparation of the Second Symphony for the Collected Edition, Carragan found crucial tempo indications by examining the individual parts that were used on the two occasions when the composer himself conducted the piece (Carragan, 2013). And in the case of the Seventh, two letters from Bruckner to Artur Nikisch sent while Nikisch was preparing the premiere performance refer to essential tempo indications which were at that time not present in the manuscript score from which he was working (see Crawford Howie, Anton Bruckner, A Documentary Biography, Edwin Mellen Press, 2002, page 405), and are today widely presumed to be those in the first edition.

Reorchestrations

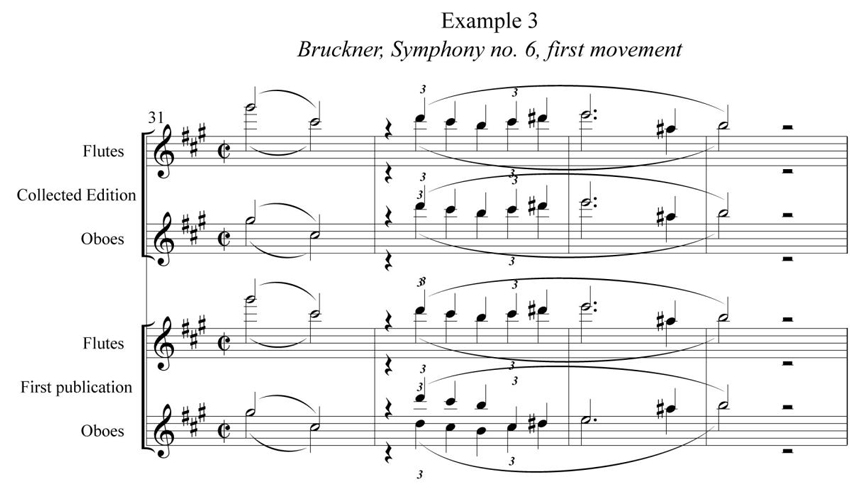

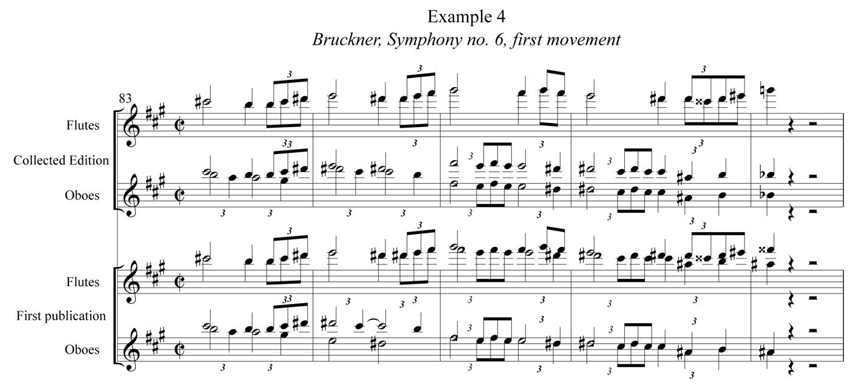

Besides the addition of copious tempo alterations, the first publication of the Sixth Symphony is also notorious for its many reorchestrations. A common difference between the Collected Edition and the first publication lies in the tessitura of the first oboe. There are more than twenty-four separate differences between the two scores concerning the first oboe in the first movement alone. In almost all of these cases the first publication lowers the part if Bruckner has written E6, F6, and F#6. Often the first oboe will begin a phrase in a certain octave, and when the editor of the first edition thought it appropriate, he would shift the oboe down an octave, as in mm. 33–34, example 3. However, not all of these changes were as simple as a mere displacement of the first part by an octave. In other cases, the editor of the first publication changes the other parts around the oboe in order to accomplish his goal, for example in mm. 84–86, example 4, the second flute part has been changed as well as the first oboe. The first publication begins in m. 84 by moving the first oboe down an octave, then in 85 having the second flute play what the first oboe originally had. Thus the countermelody is enriched at the expense of the main melody, and instead of having an oboe in each octave, both of the flutes are in the top octave and both of the oboes are in the bottom octave. The orchestration of the first publication is thus less inventive and rich than the original, because having both instruments sounding in different registers provides more variety than simply having two identical instruments play in unison.

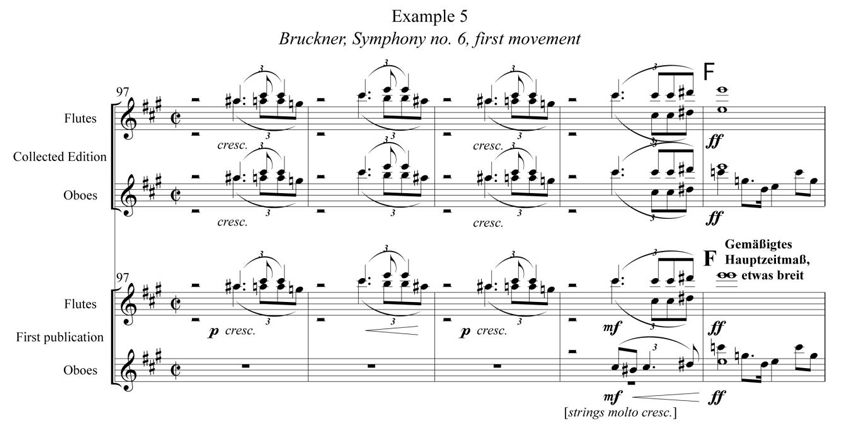

Another revision typical of the first publication is to change the instrument with which the oboe is doubling. This often leads to musical lines which are not as simple and direct as what Bruckner originally intended. Where in the Collected Edition the first oboe doubles the first flute in mm. 97–100, the first publication removes the oboes completely in mm. 97–99, example 5, and with a single oboe entering only in m. 100, right before the third theme, leading to some very awkward voice leading. These changes are in sharp contrast to Bruckner’s compositional method, which was always very attentive to accuracy of voice leading. The editor of the first publication seems not as concerned with such matters, as is evidenced by these modifications in the first oboe, as well as in other parts of the score. Note for example the difference in the first and second trombone parts in measure 202: Bruckner cross-stems the two voices to maintain the integrity of the musical line, while the first publication simply exchanges the notes to keep the higher pitch always in the first trombone.

The fourth movement oboe part has also been altered in many of the same ways. In some instances, such as in mm. 37, 53, 89, the first oboe part has been brought down the octave in the first edition to play in unison with the second oboe, whereas in locations such as in mm. 48–49, the second oboe has been brought down the octave from the first oboe; see example 6. Sometimes the editor of the first edition decided to omit the oboes entirely, which is the case in mm. 91 and 116. The case of m. 91 is of particular interest, as it shows that the editor of the first edition tried to temper the high oboe tessitura not only in louder passages, but in softer ones as well, showing that these changes in the first edition were not made in order to increase the amount of volume that the oboe could produce. Rather, it seems that the editor of the first edition believed that the timbre of the oboe in such a high register was not appealing. One of the most striking reorchestrations in the final movement includes the clarinets as well as the oboes. In m. 128 of the Collected Edition, both the clarinets play a quarter note B and have rests for the rest of the measure until their next entrance in the second half of m. 130. In the first edition, however, the clarinets and oboes sustain these notes with a diminuendo to piano. In addition, where the following measures in the Collected Edition have the clarinets and oboes playing in unison in the same octave, the first edition has both instruments playing in octaves. This undoubtebly creates a thicker, less concentrated texture, thereby making a smaller difference between Bruckner’s original fortissimo passage and pianissimo passage. By doing so, the first edition continues to mollify the distinct and startling dynamic changes of the manuscript.

In order to obtain a performer’s perspective on the issue of the tessitura of oboe parts in the Sixth, I consulted Anna Steltenpohl, an oboist in the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra and the Orpheus Ensemble. In a personal interview I presented the tessitura problem to her, and she told me that in fact the range of the oboe parts in the manuscript and Collected Edition is more or less usual. It was her belief that while an F#6 might be considered on the edge of the expected range of a professional oboe player, one should remember that Stravinsky calls for an A6 in his Pulcinella. Ms. Steltenpohl also said that there is no loss of control, color, or volume when playing the E6, F6, and F#6, and that indeed Bruckner’s music is considered by oboists to be a standard of good idiom.

These first-edition changes in the first oboe part can be seen as an attempt to make the score more accessible, but upon examination seem inferior to the original music created by Bruckner. The manuscript (and thus Collected Edition) range of writing for the oboe is not particular to this symphony, but can be found readily in both the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies which flank it chronologically. In the first movement of the Fifth, Bruckner writes E6 (mm. 85, 471, 472), F6 (mm. 296, 480), and even F#6 (m. 483), and in the Seventh Symphony, there are numerous times that he writes E6 (first movement mm. 29, 37, 102, 144, 259–260, 347, 427, 428, 429, 430, 431, 433–443) and F6 (mm. 241, 242, 243, 295). The ending of the first movement of the Seventh is perhaps the most telling example, with Bruckner making the first oboe hold an E6 for over 10 measures. The first publication of the Seventh Symphony consistently retains these high oboe notes, and does not try to modify them as was somewhat later done in the first publication of the Sixth. This also is in agreement with Benjamin Korstvedt when he labels the first edition of the Seventh authentic and the Sixth not authentic, while Deryck Cooke, in The Bruckner Problem Simplified (1969), labels all first editions “spurious” which seriously oversimplifies the case.

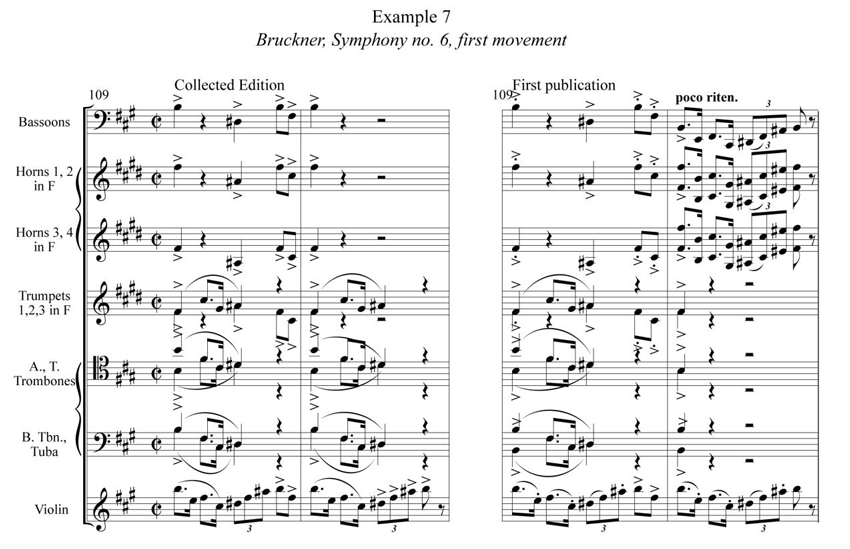

In the first publication there are other changes in orchestration besides the first oboe part. Some of these changes are not as obtrusive as others. There are numerous instances where the first publication replaces one note in a chord with a different note. The differences can be minimal, and often there seems to be no justifiable explanation (e.g. first movement mm. 38 and 40 in the first bassoon). In other cases, the first edition makes a dramatic difference in the conception of a section, as is the case with the conclusion of the first part of the third theme group, also in the first movement. In both the exposition at measures 109–110 and the recapitulation at measures 293–294, the first publication changes the final measure of a four-measure repetition to add a certain kind of emphasis. To achieve this in the exposition, as shown in example 7, the editor of the first edition both adds and deletes; in measure 110 the four horns impractically play in octaves the music that the upper winds and strings have been playing for the three previous measures, and the bassoons join them, but the other brass lines are removed. Again, the voice leading is quite awkward, especially for the third horn. While Bruckner makes it clear that this bar is to be emphasized more than the others (note the three accent marks in the Collected Edition on the triplet group in the strings that are absent from the previous three measures), the new orchestration of the first publication does not have the elegance of the original conception as shown in the manuscript. In the previous three bars, the lower brass and trumpets provided support to the upper winds and strings in the first half of the bar, and the horns and bassoons provided the same support in the second half of the bar. By making the horns and bassoons play the same line as the winds and strings in the final bar of the pattern and deleting the trumpets and low brass (with the exception of an eighth note on the downbeat), the editor of the first publication has created a sound that is not as inventive and indeed is somewhat clichéed.

One of the best-known peculiarities of the first edition of the Sixth is its repeat of the second half of the trio in the third movement, a marking which is not in the manuscript and thus is left out of the Collected Edition. While the repetition creates a more conventional structure and gives the principal horn player another opportunity to showcase the high “Eroica” E-flat, it again sacrifices the unique for the sake of making the symphony more conventional and presumably more understandable. This third movement, and in particular this trio, is one of Bruckner’s most interesting and enigmatic conceptions, and the omission of the repetition of the trio shows a composer who is secure in his abilities and flexible in his formal conceptions. On the other side of the spectrum, the first edition also suggests two places for a cut, one in the second movement, and one in the finale. In the second movement, it is suggested to cut out the recapitulation of the B theme group, which would result in a lopsided form and a tragic loss of beautiful music. In the finale, the first pianissimo bars of the coda, in F minor, are suggested to be cut, which, among other problems, would result in an ill-placed non-sequitur from the dominant of F major to A major (a problem which the editor says can be avoided with the addition of a “Luftpause”; however, it is clear that this solution is not satisfactory). Both of these potential cuts are harmful to the musical structure, and thankfully it does not seem that the majority of conductors who perform this piece would even consider them.

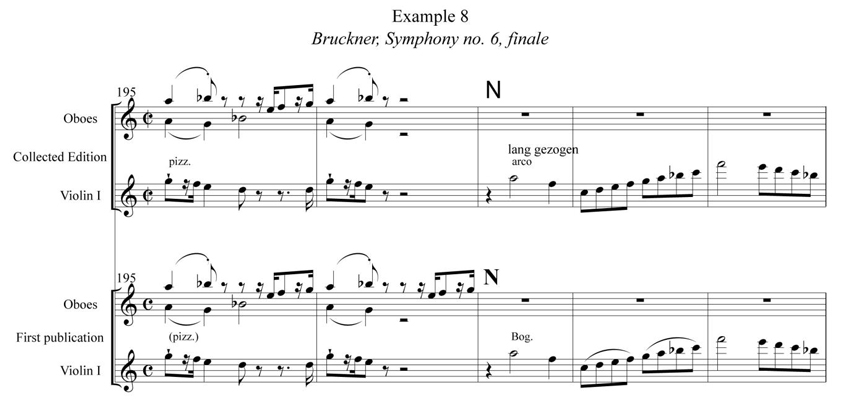

A curious change in the first publication can be found in the addition of a bit of new composition early in the development of the finale1 . In m. 196, before the strings’ lyrical transformation of the A1 theme in F major, there is an isolated pickup based on the preceding theme of mm. 186-196 in the first oboe. In the Collected Edition, there is nothing but silence; see example 8. Only a further examination of the sources could clarify this discrepancy, but to add such a phrase was well within the capability of Josef Schalk.

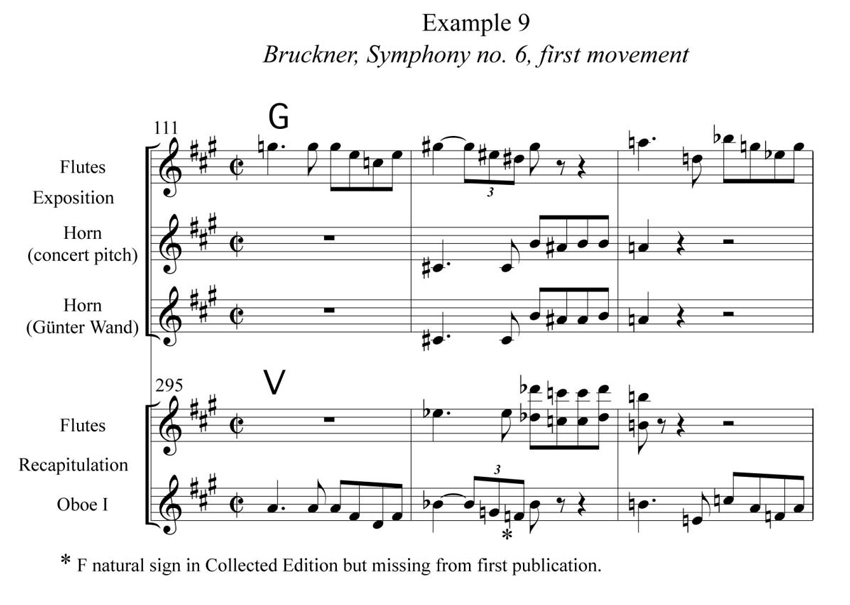

While the first publication is replete with dubious reorchestrations, there are two instances in the Collected Edition which also prove to be problematic. The first appears in m. 112 in the first horn, where Bruckner has written on the second beat the following four eighth notes (in concert pitch): B Bb B B, where in the analogous passage in the recapitulation, both flutes play at m. 296 in octaves the following four eighth notes: Db C C Db (Nowak, 1952). This inconsistency is not the fault of either Nowak or Hynais or Schalk (or Haas, for that matter), as the manuscript (Austrian National Library Mus.Hs. 19.478) clearly shows both passages, from which there can be no doubt as to what Bruckner wrote on paper. The distinguished Bruckner conductor Günter Wand was the first to call attention to this difficulty, and in his recording of 1995, he changed the horn passage in the exposition to follow the contour of the flute passage in the recapitulation, see example 9. William Carragan agrees with this change, and believes the manuscript notes to be an uncharacteristic oversight on the part of the composer (Carragan, 2013).

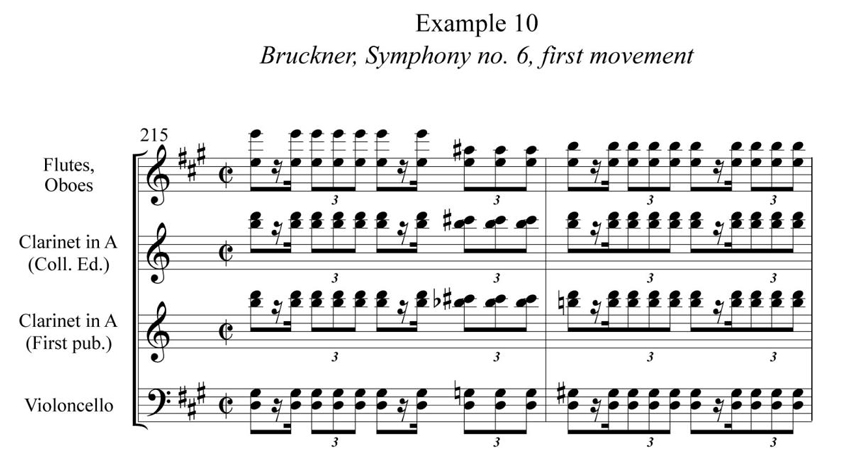

The other problematic area is at the beginning of the recapitulation, in the second clarinet part in m. 215, where the collected edition shows B B B (sounding G# G# G#) on beat 2.5, where the first publication shows B flat B flat B flat (sounding G G G), as shown in example 10. Harmonically, the Collected Edition notes do not fit with the harmony being produced on that beat by the violoncellos. Furthermore, the harmony on beat 2.5 is one that is not found in the simpler scoring of the corresponding measure in the exposition (m. 33), which is much closer to a pure dominant, Bruckner having changed the music at the recapitulation to be more harmonically inventive and urgent. The manuscript supports this notion, which is full of erasures in this section. The manuscript shows in m. 215 small markings above the second clarinet notes in question, which could possibly be construed to represent flat accidentals, which would make the manuscript agree with the first publication and the Collected Edition would be wrong. Whether this problem is the fault of the composer or subsequent editors is irrelevant to the fact that the notes should be rendered as they appear in the first publication, with the second clarinet consistent with the cellos and thus with the rest of the orchestra.

Dynamics and articulation

Of the over 1200 differences between the two publications in the first movement, over half of them concern dynamic markings and expressions. The dynamics in the first publication mainly serve to dull the sharp and vivid contrasts that are a hallmark of the manuscript, and to give specific dynamics to certain instruments where the manuscript gives a universal dynamic. In order to achieve these goals, the first publication goes as far in certain cases as to give a completely different dynamic marking at crucial moments in the piece. Again, the arrival of the third theme group is a point of interest. In the exposition, the dynamics in m. 101 are basically consistent between the two sources, with the exception of ff being replaced by f in the trumpets in the first publication. Startlingly, the first publication accompanies the same material in the recapitulation with the indication “pp cresc. sempre”, even though the Collected Edition has ff in every part, as was the case in the exposition. Because in the recapitulation Bruckner does not give music corresponding to the four measures of crescendo which precede m. 101 in the exposition, it seems as though the first publication tries to eliminate the shock of a sudden orchestral fortissimo by starting the third theme group with a pianissimo. However, throughout the whole symphony, the Collected Edition indicates that Bruckner wants this sort of shift in dynamic to be sudden.

There are no major dynamic negations in the fourth movement of the first edition such as those are present in the first movement, but there is the general sense of softening Bruckner’s original stark dynamic contrasts. As was the case in the first movement, there are numerous dynamic additions, not in the Collected Edition, which can help the performer and the conductor shape the phrases. For example, in m. 390 during the coda of the movement, the first edition calls for a diminuendo, followed by a series of terraced dynamics, with a “mezzo-forte” in m. 391, a “forte” in m. 393, and a “fortissimo” in m. 395. While one might argue that a sustained fortissimo for the entire passage could be quite exhilarating, perhaps the advice given by the first edition might help shape this passage and make it even more exciting.

This idea that Bruckner’s original dynamic conceptions need to be softened is not only seen in the first publication of the Sixth Symphony, but in other first publications, such as that of the Second Symphony (Carragan, 2005). We know that Bruckner strongly emphasized the abrupt terrace dynamics in his performances of the Second Symphony, as revealed in copious pencil notations in the parts, which suggests that the softening modifications in the first publication of both the Second and Sixth Symphony should be rejected (Carragan 2013). But in many instances where Bruckner’s dynamic indications are unusually bare or vague (mm. 30, 31, 32, 82, 83, 164, 178, 203, 217, 219, 220, 270, 271), the addition of new dynamics in the first publication is revealing to the student and helpful to the conductor.

While the modifications present in the first publication in terms of dynamics generally soften the original intent, changes regarding articulation both soften and make more harsh what is presented in the collected edition. The difference between the keil (vertical solid arrowhead) found extensively throughout the Collected Edition and the staccato (dot) that replaces it in the first publication pervades the entire movement, from the opening to the final bar. These two markings are not interchangeable, although many publishers do not try to distinguish between the two, using the staccato as the default. The problem with that particular solution is that the staccato does not imply the same weight as the keil, nor does it imply the same fractioning of the value of the note, and therefore the keil should be used rather than the staccato if the composer so specifies.

While the decision in the first publication to use the staccato softens the presentation of the work, there are also new articulations introduced into the first edition such as the cap accent, which seems to indicate a heavier or more emphatic sound, in the brass and upper string parts beginning at first movement m. 33 and the analogous location in the recapitulation (m. 220), and in the trumpets, trombones, upper winds and upper strings at m. 40. However, where the editor of the first publication probably thought that the brass would overpower the rest of the orchestra (i.e. trumpets in mm. 175–176), he changed accents clearly written by Bruckner in the manuscript into tenuto markings or completely removed them.

The problem of distinction between the keil and the staccato is heightened further in the final movement of the first edition. Beginning in m. 47, the marking which was written into the first edition is in shape and size between a true keil and a staccato. To make matters worse, the lack of consistency with which the marking is written makes it even harder to distinguish whether or not it is to be interpreted as a keil or a staccato. However, there are clear examples, such as in m. 208 where the editor of the first edition uses staccatos and the Collected Edition uses keils. On inspection of the manuscript it seems to me that it could be interpreted either way.

Just as the staccatos in the first publication lighten the overall impression, so too do the publication’s modifications in regard to note duration. In every instance, the first publication has a shorter value. Often at the end of phrases, as at m. 104, the first publication changes Bruckner’s original quarter note to an eighth note, eighth rest. In measures where Bruckner writes consecutive dotted-eighth note and sixteenth note cells, the first publication has eighth note, sixteenth note rest, and sixteenth note cells. Both of these changes demand a lighter style of playing that the original scoring does. And while it is not prudent to make such changes without the composer’s intent, these changes suggest that original performances of this work were lighter and, by implication, faster than those usually encountered today.

Conclusion

Despite its many debatable and adventurous modifications, the first publication for all its faults can be very useful to study for those wanting to improve their understanding of this enigmatic work. In his forward to his contribution to the Collected Edition, Nowak writes the following: “…[T]he inaccuracies and discrepancies [present in the first and subsequent editions] may well be the reason why the Sixth Symphony has lagged behind some of the others in popularity; quite undeservedly so, because its spirited straightforwardness, its wealth of serene melody, and its imperious rhythms fully entitle it to a parity with all the other symphonies” (Nowak, 1952). While this statement rings true over fifty years later, the symphony is now suffering from quite an opposite stigma, that of over-sterilization. In fact, it can be said that neither the first-published edition nor the Collected Edition is wholly good or wholly evil. Rather, both have aspects that can inform the student and performer of the correct way to conceive of the symphony, and at this point in the editing history of the symphony, it is only through a complete study of both texts that an informed vision of the piece can be construed.

Leave A Comment